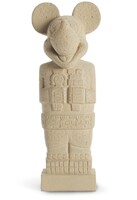

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the Colombian artist Nadín Ospina created works that replicated object types associated with various Pre-Columbian cultures while replacing the original imagery with contemporary popular culture icons such as Mickey Mouse and Bart Simpson.

Nadín Ospina, Artworks (1990s-2000s)

The result is an ambiguous yet powerful statement on the nature of cultural production and consumption. Ambiguous because, as with his Pop Art forerunners, it remains unresolved whether Ospina held a critical or celebratory stance to the iconography he appropriated. The insertion of cartoon characters into the formats of solemn and often sacred traditional artworks makes visible the latest manifestation of cultural imperialism that has continued a process of subjugation begun in the mid-16th century. Moreover, the integration of disparate sources of past and present imagery simultaneously points both to the status of these ubiquitous animated beings as the new idols of a globalized Modernity and to the transformation of the archaeological past into a theme-park-like attraction. But these critical undercurrents are belied by the artist’s own statement that, apart from their ethnicity, the modern residents of Latin American countries have no more connection to these ancient civilizations than someone from the other side of the world. Rather, according to Ospina, the contemporary inhabitants of the regions once occupied by the cultures who produced the objects upon which he based his artworks almost certainly feel a greater connection to modern Disney characters than to sculptures made many centuries ago. Thus, the fusion of modern cartoon characters with Pre-Columbian styles can be read as both a humorous juxtaposition of the familiar with the exotic as well as a serious reflection on the question of how we relate to the past, and, by extension, on what archaeologists from the distant future will make of our current material culture.

These sculptures additionally problematize notions of authorship and authenticity. This is because Ospina didn’t make the pieces himself, but rather commissioned them from locally renowned artisans from the regions in which the prototypes originated––the same individuals who were already producing objects for sale within a grey market where the lines between tourist art, replicas, and forged antiquities are notoriously blurred. While Ospina made specific requests as to the nature of the artworks he commissioned, he also allowed the individual sculptors significant latitude in carrying out their assignments. The final product is therefore an “authentic” Nadín Ospina artwork that was produced by a master forger. Furthermore, as testament to the abilities of these craftsmen to accurately simulate their Pre-Columbian prototypes, the curator Virginia Pérez-Ratton issued Ospina with “falsehood authentication” papers after his show at TEOR/éTica in Costa Rica so that he would not be accused of smuggling antiquities when leaving the country.

____________________________________________

More on Ospina can be found on the artist’s website and in the following sources:

- Nadín Ospina: La suerte del color. Ediciones El Museo (Galería El Museo, Bogotá / Galería Fernando Pradilla, Madrid), 2014.

- Jaime Cerón, “A Post-Columbian Art,” in Pre-Columbian Remix, ed. Patrice Giasson. Purchase, NY: Neuberger Museum of Art, 2013.

- Virginia Pérez-Ratton, “The Art of Authentic Fraud,” Prince Claus Fund Journal 10 (2003): 100-107.